what did black political leaders accomplish and fail to accomplish during reconstruction?

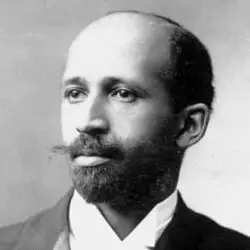

W.Due east.B. Du Bois, author of Black Reconstruction in America (1935)

The Reconstruction era of United States history has spawned renewed involvement. It has go a critical period to study because it helps us understand the nature of political representation and the nature of democracy in moments of crisis. Coming later on the Ceremonious State of war, Reconstruction was the flow that attempted to settle the question of the Confederate states' re-entry into the union while likewise dealing with the question of the citizenship of four one thousand thousand Blackness freedpeople.

At the core of these questions were both the idea of Black voting rights and the potential service of Black politicians. Meaning political leadership on both the federal and state levels emanated from the Black community. Some of the more famous of these leaders were Hiram Revels, P.B.South. Pinchback, and Robert Smalls. They offered an enduring legacy in helping legislate into existence policies on educational activity, ceremonious rights, and economic reforms.

How the History Has Been Told

The story of Reconstruction had either been neglected or distorted for several generations after it concluded. Much of the neglect and baloney continues, but it was to the credit of West.E.B. Du Bois and his awe-inspiring effort, Black Reconstruction in America (1935), that the record of Blackness politicians became clear. Against the tendency of looking at their political service as disastrous and "rightfully" macerated by what Southerners called Redemption, Du Bois argues forcefully that they helped establish some of the most egalitarian political initiatives in American history. For they were ushered in during a period where republic was expanded in ways that was every bit transformative as any other catamenia for it enfranchised those who had been enslaved less than a decade before. For Du Bois, it would stand to reason, then, that when given the opportunity to occupy political office that they would do something different, that they would try to create a political environment that was grounded in equality instead of repression.

In challenging this hierarchy, these politicians also managed to inspire a negative tradition of "Lost Cause" historiography, which saw Black political ideas every bit necessarily antagonistic to a Southern way of life. This framing has created much confusion effectually what actually happened during the period, even inspiring perchance the most of import blockbuster in the history of American movie theater, The Nativity of a Nation (1915).

The story that Du Bois told, so, was scarcely told, though there were some rare exceptions—a notable ane being John R. Lynch'due south The Facts of Reconstruction (1913)—that detailed the role that Black politicians played in developing a new vision of republic in the United States. In more than recent years, scholars like Lerone Bennett, Jr., Vincent Harding, Thomas Holt, Eric Foner, and many others accept taken Du Bois every bit a straight inspiration in their own narrations of what truly happened during Reconstruction.

The Emergence of the Black Political leader

The story of the emergence of the Blackness politicians begins in large measure while the Civil State of war was going on. Every bit the Union ground forces conquered territories in the South that were under rebellion, scores of enslaved Africans achieved freedom by flocking to their lines. This constituted a "political problem" for the United states that eventually led to Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Black leadership naturally emerged within this context. For instance, Garrison Frazier, a Blackness government minister, was the leader of the community of freedpeople in Savannah, Georgia. When he and his boyfriend ministers were approached by the Secretarial assistant of War, Edwin Stanton and General William T. Sherman well-nigh their "needs" in early 1865, they responded that they were concerned to acquire education, land, and protection. Frazier was never voted into any role but his story, representative of the larger Black customs, is important because it helps united states run into what political questions most concerned Black people at the finish of the war. Information technology would be incumbent upon those who did achieve political role to translate these concerns into effective policy.

The opportunity to practise so came with Congressional Reconstruction. Under the Reconstruction Human activity (1867), all citizens nether the Fourteenth Amendment (which included freedpeople), would be given the opportunity to make up one's mind on convening a ramble convention and selecting delegates to that coming together. It was here where newly emancipated Blacks began their rising to political office as many of the delegates that helped craft new constitutions in united states of america were chosen past their beau customs members. Black politicians were then in a fortuitous position when it came fourth dimension to run for elected office within these state legislatures as they became well-known and well-liked equally a result of their service in the constitutional conventions.

Service in the State Legislatures

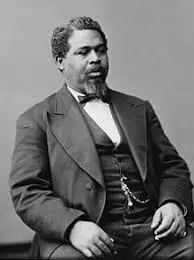

Robert Smalls, state legislator and Congressman from South Carolina

Our first glimpse of what these political figures accomplished can exist seen in the various country constitutions that they had a hand in developing. In Southward Carolina, Black politicians argued for civil rights protections too every bit educational provisions as responsibilities of the state. Afterwards beingness elected to the state legislature, Robert Smalls was one of many Black officeholders who championed the need for education of the newly emancipated Blacks. For Smalls, and others, teaching was a necessity to forestall any return to a nominal form of slavery that many saw equally possible. He had rose to fame later on commandeering a Confederate transport, The Planter, in 1962 and steering it directly to the Union navy. With that deed of heroism, Smalls began a long career as a Black political leader and instruction was an issue never far from his agenda as he helped in the establishment of South Carolina State University, the state'southward but public historically Black college.

This was also truthful of some other disquisitional state-level leader, Jonathan C. Gibbs. In Florida, at that place was no majority Black presence as in that location had been in South Carolina, which made things more difficult for the Black customs. Forced to make strategic alliances wherever possible, leaders like Gibbs parlayed these experiences into achieving important positions. For Gibbs, that position was the Superintendent of Education, where he was able to ensure that Blackness students received an equitable instruction in the immediate aftermath of the abolition of slavery, fighting to establish what is now the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical Academy, ane of the country's largest historically Black colleges. A Philadelphia native. who like many gratuitous Blacks, came to the South near the finish of the state of war, Gibbs had also previously served equally Florida'due south secretarial assistant of state becoming one of the most important leaders of any hue in the state.

One of the more visible Black leaders was Louisiana's P.B.S. Pinchback. The son of a white Macon, GA planter, Pinchback would somewhen end up serving in Louisiana'southward Native Baby-sit during the state of war. From there, he was able to go a formidable political figure in the contentious environment that marked Reconstruction-era Louisiana. This was a state that had a big Black presence, every bit well as a group of mixed race individuals that occupied somewhat of a middle or buffer position in the land. Together, these groups represented a challenge to the white supremacist norm that was often met with mob violence. The massacres in New Orleans and Colfax are egregious examples. And where violence did not work, an especially obscene version of the Blackness Codes held sway, especially in Opelousas, Louisiana.

Therefore, politicians like Pinchback faced an uphill boxing in ensuring that Black rights were protected and the democracy translated into better weather for all. Every bit the Republicans sought to control the procedure of Reconstruction, Pinchback was one of the Blackness politicians that rose to ascendancy, serving in the Louisiana Land Senate. In that location he, much like Smalls and Gibbs, strongly supported educational policies for Blacks. Rising to president pro tempore, he was side by side in line to serve as lieutenant governor when Oscar Dunn, the sitting lieutenant governor died. When the governor, Henry C. Warmoth was impeached, Pinchback became the governor of the country for a cursory period of time, becoming the kickoff Black governor of any U.S. state. He would eventually exist elected to the U.Southward. Senate, though prevented from sitting, and finally played a office in the establishment of Southern University, one of Louisiana'due south largest historically black colleges.

These are but three examples of the complex roles that Blackness politicians played in the era of Reconstruction at the state level. While Smalls, Gibbs, and Pinchback were all involved in educational policy, others on the country level sought to redistribute land and wealth, develop fairer policies around labor contracts, forestall the captive leasing organisation, create land-level civil rights protections, and ensure voting rights. In each country, however, their work was undermined through mob violence, the duplicity of the Republican party (their erstwhile allies), and a failing economic system exacerbated by the monopolistic system of the railroad companies. In the histories prior to the work of Du Bois, Blacks are blamed for these failures, just nosotros know now that the picture is varied and complicated.

Political Piece of work on the Federal Level

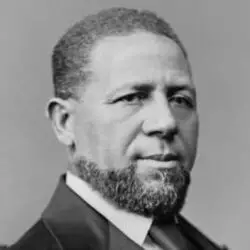

Hiram Revels, the first Blackness Senator, representing Mississippi

A number of Black politicians made their mode to service in Congress. According to Du Bois, the principal issue on their agenda revolved around securing "themselves ceremonious rights, to aid education, and to settle the question of the political disabilities of their former masters." They "advocated local improvements, including the distribution of public lands, public buildings, and appropriations for rivers and harbors…" [one] A lot of this work sought to use the power of the federal regime to aid in the transformation of the country through redistributive policies. As such, the legacy of the politicians who served in Congress was one of imaginative economical reform. Members of that grouping include the first Blackness senator from Mississippi, Hiram Revels, as well as the same Robert Smalls and John R. Lynch, and finally, important figures such as Blanche K. Bruce, Joseph H. Rainey, and Robert C. DeLarge.

By the mid-1870s, the political context had shifted. The Northern industrialists having gotten a foothold into the economical systems of the Due south, began to withdraw their support for the Black vote and for these economic reforms. Along with the violence that never abated, Blackness politicians struggled to bring domicile many of the promises that their political ideas portended. With the Panic of 1873, things came to a head. By the 1876 election, much of the political vision of Black and progressive/radical politicians was on the wane and Reconstruction came to a shut with the Compromise that settled that year'south election.

Conclusion

This brief foray into this little-known history of Black political activity in Reconstruction reveals the complex forces at play also equally the resilience of a people who not simply endured slavery but fought their way out of those conditions to develop a political praxis that accomplished much. Though cursory, information technology was intense and transformational. Perchance its lasting legacy is the public education system and the existence of historically Black colleges and universities to this mean solar day. Its unfinished work and perhaps its current relevance is the vantage point that it articulated from the highest political offices of a vision of democracy for those traditionally excluded.

Bibliography

Du Bois, W.E.B. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.New York: Gratis Press, 2000.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper, 1988.

Harding, Vincent. There is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Caryatid, 1981.

Holt, Thomas. Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in Southward Carolina during Reconstruction. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the Civil War. New York: Russell and Russell, 1953.

References

- ↑ Due west.E.B. Du Bois, Blackness Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (New York: Costless Press, 2000), 628-29.

Admin and J-intellectualhistory

Source: https://dailyhistory.org/What_Did_Black_Politicians_Accomplish_during_the_Reconstruction_Era

0 Response to "what did black political leaders accomplish and fail to accomplish during reconstruction?"

Post a Comment